Sarah Grilo

by Karen Grimson

Art historian (Courtauld Institute of Art, London)

Sarah Grilo, Azules y violetas, 1961. Oleo sobre tela, 162 x 146 cm. Colección Pampa.

Azules y violetas [Blues and Violets], 1961

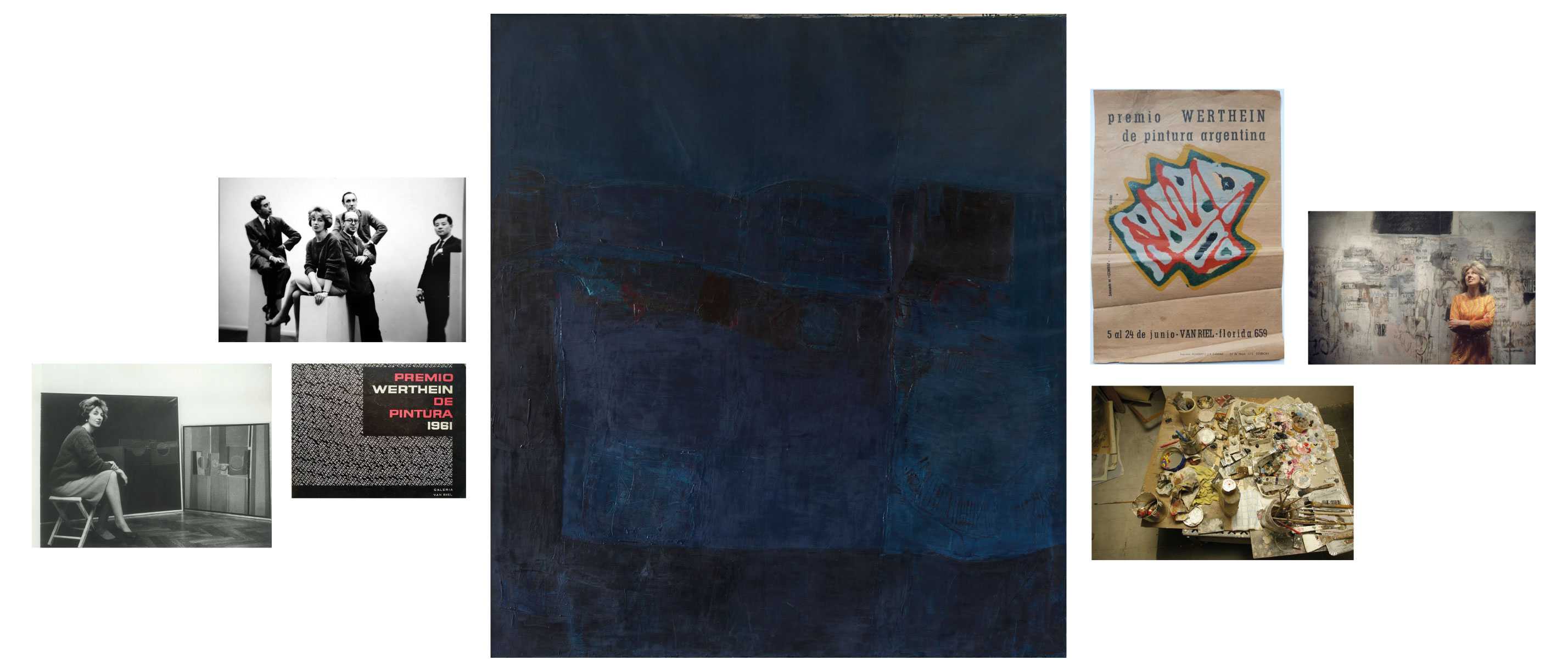

A single and dense fabric, infused in underwater darkness tones, bears a very personal imprint in its textural variations. Painted in April 1961, Azules y violetas [Blues and Violets] is a classic example of the chromatic abstraction found in Sarah Grilo, once called “the great colorist of her generation.”1

In those years, when the novelty of Argentinian painting was hesitant between Informalism and New Figuration, the artist was prone to project her subjective formal explorations onto the surface, enlivening the canvas with an intuitive palette and a great gestural spontaneity.

Atelier de Sarah Grilo, Madrid, 2007. Fotografía de Juan Muro.

Sarah Grilo is a central personality in the history of Argentinian art. Over the course of a career spanning more than seven decades, she produced a prolific body of work crossing the passage from abstraction into modern and contemporary painting.

Sarah Grilo, 1960. Fotografía de Diana Levillier.

During the fifties, Grilo was a regular in Buenos Aires’ artistic circles, and played a key role in the path to make Argentinian abstract art recognized through international exhibitions and submissions to biennials. Between 1952 and 1955, invited by art critic Aldo Pellegrini, she was a member of Grupo de Artistas Modernos de Argentina, a coalition of non-figurative artists that gathered the most fervent supporters of concrete art together with other independent abstract artists. A few years later, after having been a participant in the Buen Diseño para la Industria [Good Design for Manufacturing] collective, Grilo was included in the 1960 exhibition Cinco Pintores [Five Painters] at Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, excelling at both endeavors as the only female artist.

Grupo de los Cinco: Miguel Ocampo, Sarah Grilo, Clorindo Testa, José Antonio Fernández-Muro, Kazuya Sakai.

Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, 1960. Fotografía de Diana Levillier.

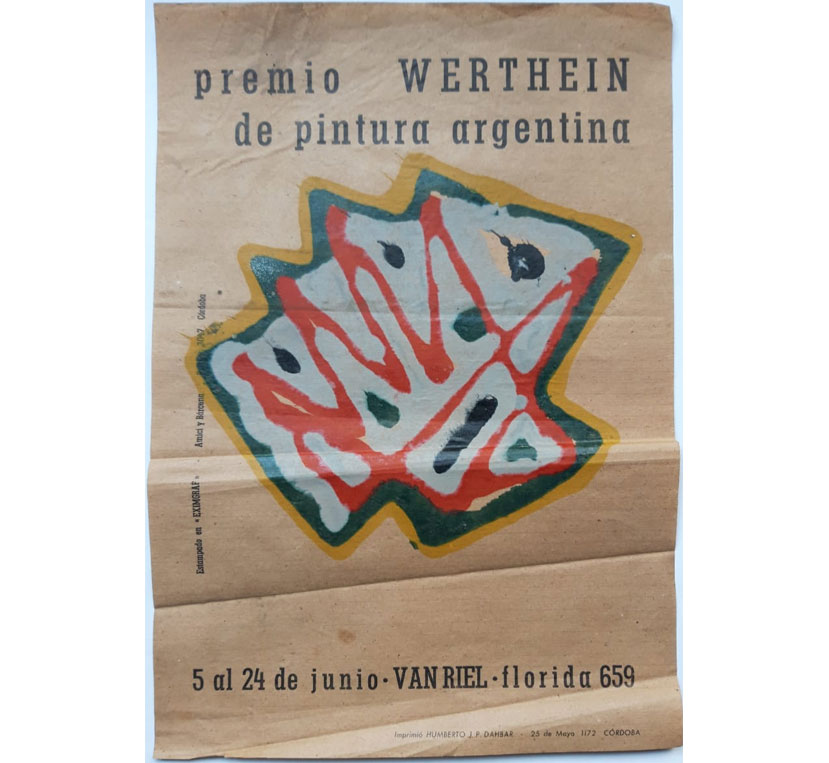

By 1961, those who hanged around the manzana loca [crazy block, where art galleries, the Di Tella, fashionable stores and bars were located] would have been able to see Grilo's work at Instituto Torcuato Di Tella and Galería Bonino. Besides, the nearby Galería Van Riel showed works from Premio Werthein de Pintura Argentina [Werthein Argentinian Painting Award] that same year in June.2 Azules y violetas, a work that marked a pivotal instance in Grilo's artistic career, was among them. A few months later, with a grant from the John S. Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the artist embarked on a trip to New York, starting the initial chapter of her permanent voluntary exile. Outside Argentina, she would soon give up this kind of abstraction (often called ‘lyrical’ to differentiate it from intransigent orthodox abstract painters) and would swing over to some sort of expressionism strongly linked to pop art; its linguistic and calligraphic infusion united her in an embrace with the contemporary reality of her everyday life.

Catálogo de la exposición “Premio Werthein de Pintura” en la Galería Van Riel, Buenos Aires, 1961.

Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Archives, New York.

Poster de la exhibición “Premio Werthein de Pintura”, Galería Van Riel, Buenos Aires, 1961.

Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Archives, New York.

Como tal, As such, Azules y violetas is the vestige of a crucial era when the local scene, increasingly in dialogue with the international field, detached itself from the legacy of Concrete art and geometric abstraction that had championed the development of visual arts in the previous decade. The traces – perhaps the shadows – of quasi-geometric zones, circular and semi-orthogonal spaces that wander between geometry and rhythmic undulation, nucleated in a dynamic center with structuring margins, can be glimpsed in Grilo’s canvas. Capciously close to monochrome, the work entered the already so worn-out search for the underlying value of painting; an inquest that used to be mistaken for some kind of international abstract Expressionism 3in those days.

Grilo had been challenging the orthodoxy of illusionist representation in her work for some time. However, in 1969, Jorge Romero Brest, then Director of the Centro de Artes Visuales at Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, wrote that “Sarah Grilo was by 1960 a strange post-cubist painter,”4 exposing an institutional inability to inscribe the artist's career within an autonomous variant. Even towards the end of the decade, Grilo's work was perceived as a deferred expression of the experiences previously developed by the historical avant-garde. This interpretative anachronism, which still prevails today, echoes a certain historiographical discomfort to inscribe her production within the existing categories. After all, Grilo remained independent, even when working in partnership; she was too lyrical for the Concrete artists, too intuitive for Programmatic artists, a little late for Abstract Expressionism, and too pictorial for Informalism. Uniquely equal to herself, Sarah Grilo's career is enlisted in a narrative that remains, even today, fervently sovereign.

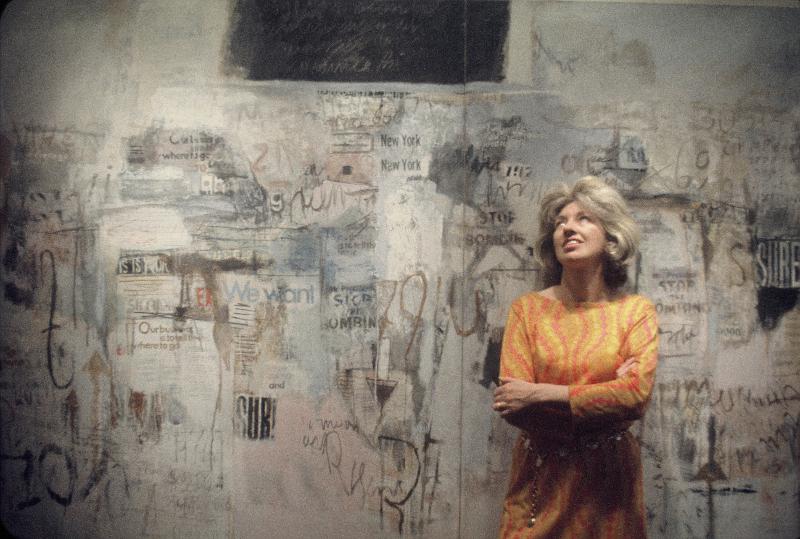

Sarah Grilo frente a la obra Mr. President en su exposición individual en Byron Gallery, Nueva York, 1967.

Fotografía de José Antonio Fernández-Muro.

1 Damián Bayón, “Cuatro pintores argentinos de Nueva York” [Four Argentinian Painters from New York], La Nación, December 6, 1964.

2 Ernesto Ramallo. Premio Werthein de Pintura Argentina [Werthein Prize for Argentinian Painting], Buenos Aires, Galería Van Riel, 1961.

3 See a review of Modern Argentine Painting and Sculpture show at the Scottish National Gallery of Art, Edinburgh, in Cordelia Oliver, “Art from the Argentine”, The Guardian, London, June 7, 1961, p. 9.

4 Jorge Romero Brest, Arte en la Argentina: Últimas décadas [Art in Argentina: Last Decades], Buenos Aires, Paidós, 1969, p. 40.

Karen Grimson (Buenos Aires, 1986), Bachelor of Arts from Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires, with a master’s degree in art history from the Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Between 2011 and 2020, she worked at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where she collaborated in the development of acquisitions and exhibitions of Latin American art, such as Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern; Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil; and Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction. The Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift, among others. She published texts in the books Among Others: Blackness at MoMA, Being Modern, MoMA Highlights, and Joaquín Torres-García; she authored articles for the Magazine and Post websites, and taught courses on Brazilian modernism at MoMA. She curated the exhibition Pablo Gómez Uribe: All That Is Solid at Proxyco Gallery in New York in 2018 and was co-curator for the Colombian contemporary art group exhibition Archipiélago Medellín at Sala Suramericana.