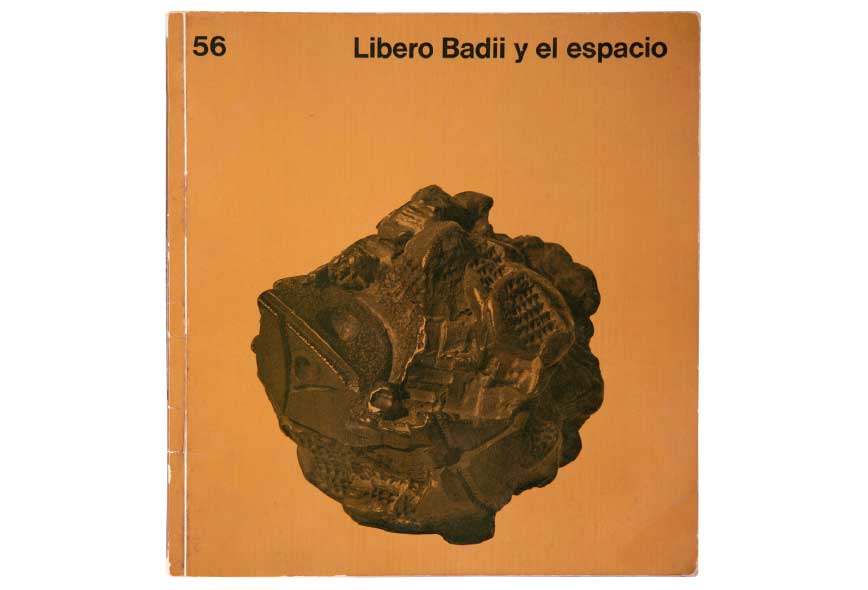

Libero Badii

by Santiago Villanueva

Curator, Public Programs and Education at Malba

An alliance with the remains

Libero Badii conceived his work as communication through materials. And the material would be the possibility of keeping a state prior to ideas, to entrust in art the sneaky, slippery existence prior to the word.

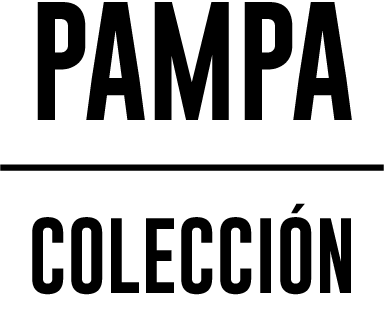

Libero Badii, Restos Cinco, 1978. Aluminio, papel y cartón 17 x 32 cm. Colección Pampa.

If Badii ruined much of what he did with words, he also allowed himself not to avoid commonplaceness. In Restos cinco [Remains Five], and Sin Título (arte siniestro) [Untitled (Sinister Art)] we see the pretension and the precariousness, and like many of his sculptures of the fifties, it operates as a structure of thought for the unstable times of art in Argentina. Matter is a feasible way out of geography: avoiding references, becoming uncomfortable with the place, depending on a discourse that is positioned there just to apply pressure on typical thematized forms. Badii opens and sustains the sinister matter line, that is, the one so well-known that becomes alien and even dangerous. Right there, what he thinks of the work becomes clear: the possibility to bend the material, until they grow familiar and terrifying at once.

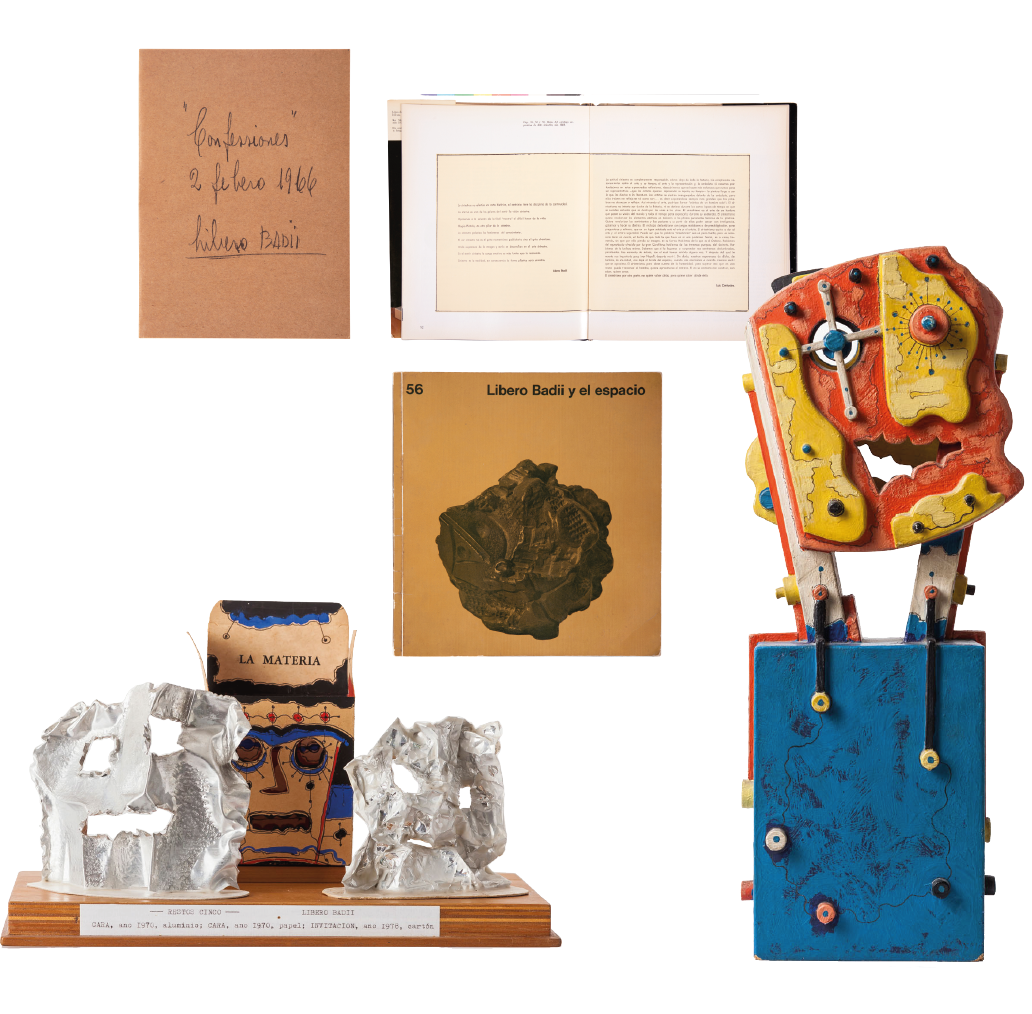

Libero Badii, Sin Título (Serie Arte Siniestro), 1978. Madera Policromada 55 x 21 x 21 cm. Colección Pampa.

Sinister, as defined by Badii, is as broad as it is confusing. He imprints a quality of movement to the concept of sinisterism, that term from psychoanalysis, but it was originally further linked to pre-Hispanic traditions and the opposition between the known form and the unknown form, or the form to be known. The sinister has multiple means to present itself on hand: one of them is the “suspense technique,” delaying the appearance or the completion. The sinister thing is to advocate for the absence of concrete communication (“I hear a voice, it is not any technical communication, it is the sinister voice”). For Badii, “the American reality” was that familiar unknown thing, and beyond some totemic presences, he assigns this capability for surprise to the material, as a prospect of what he calls “communicative irradiation.” This is generated by working with the same shapes and dissimilar materials, the influence of light produces “mystery of irradiation in the forms!” The repetition of motifs, vases, or masks, between metal, paper, or cardboard, will allow him to show in an effortless way the irradiation variables. In Restos cinco the word ‘matter’ is printed in the center of the object, and the small face-box containing it is guarded by two other faces made of aluminum foil. There is evidence of the change development, whose direct reference is also Víctor Grippo’s work, where not only the materials but also the used tools are seen, through active transformation sequences.

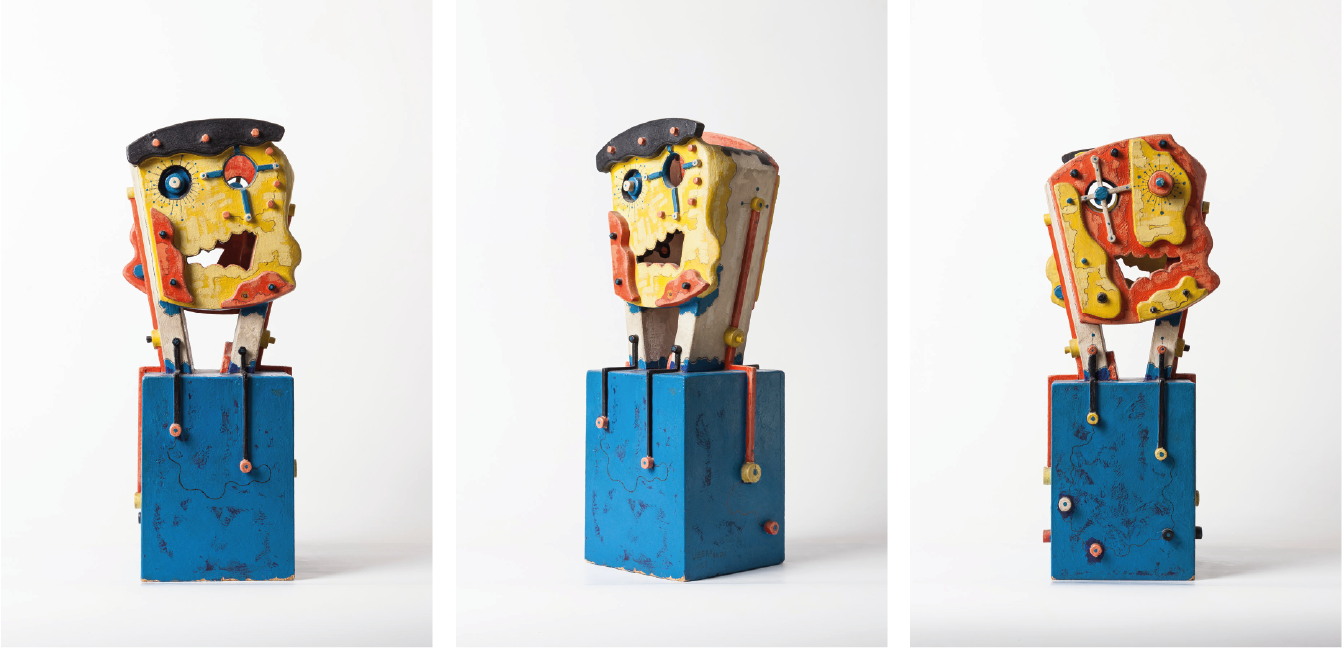

Libero Badii, Confesiones, 1966. Gentileza Malba. PH: Nicolás Beraza

Between a therapy for the ego, and an alchemy of materials, Badii is the one in the middle between Alberto Greco, Liliana Maresca, and Mónica Girón, or next to Emilio Renart. But one of the dissimilarities is that Badii, like many artists of his generation, looks at pre-Hispanic cultures, with its problematic distance for an answer, to something “of his own”, disappointed by the avant-garde, in search of another norm, or to bring together several norms to work from an organism of contradiction. The cardboard from a disassembled box, the aluminum foil from a chocolate wrapping, perhaps the painting by hurried stains, are small decisions to turn the great ideas of art fragile, those unfathomable concepts that Badii will never dispose of. A sentimentality of materials to supplement the fall of the avant-garde.

Libero Badii, Arte siniestro, 1979, Gentileza Malba. PH: Nicolás Beraza

I think of the remains, of what is left over or overflowing, as something that brings out the center, or makes it dizzy, because what escapes from the confining form is often a necessary surplus. Something happened to Badii, like Yente (Eugenia Crenovich), with the works made towards the end of the seventies and beginning of the eighties: some are made with fabric scraps, others with Styrofoam (employing packaging for electrical appliances). What did not find a function, because it contained something or had no use, was likely to become art.

Emilio Renart also thought of communication as a therapeutic possibility, and that means something that can be constantly reset, and the means to get hold of the work, as a space for group communication, beyond art. That is, he thought that art opened new circuits of communication, otherwise impossible to know, and that this communication is a healing instance.

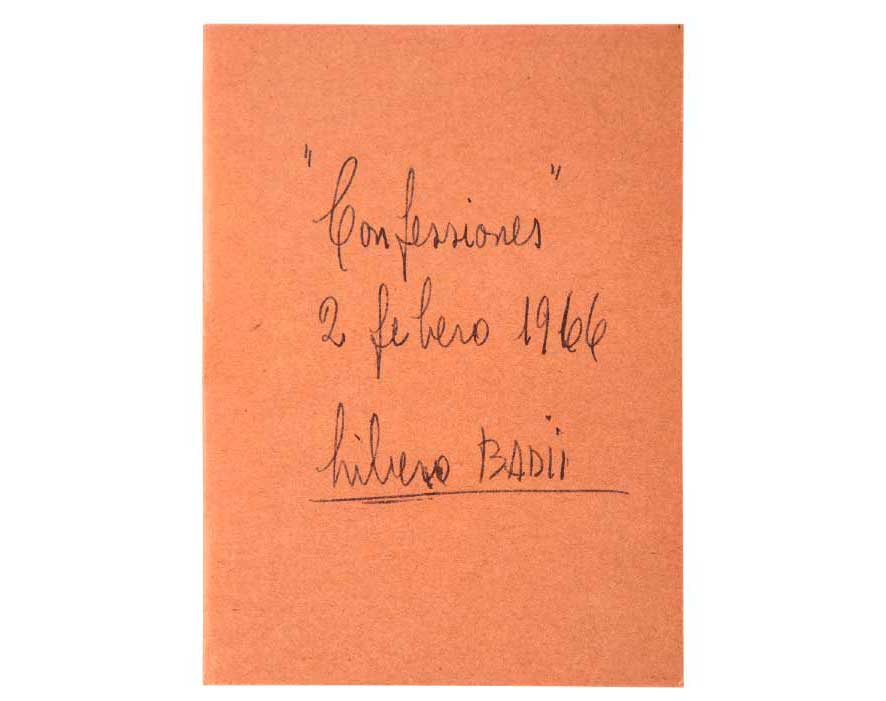

Catálogo de la exposición Libero Badii y el espacio. Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, 1968.

Gentileza Malba. PH: Nicolás Beraza

Badii’s sinister nature can be perceived akin to Renart's concept of creativity, which he developed due to the death of his daughter Graciela. Since 1969 Renart created a series of “coexistence exercises” to be conducted with his family, but he used them with diverse groups of art students afterwards. The collective exercises had drawing and words as their central axis, as a group, activating the paper through certain choreographic guidelines: rotating the base, working from the inside out, etc. Both sinister art and the concept of creativity pursued alternative forms of communication.

If we look at Renart and Badii’s body of work, far from labels and close to therapeutic actions, we can understand that both embrace contemporary art. Within the work’s communication/non-communication, through the materialities, between the edges’ construction and destruction, lays that possibility of invention with the remains, with what is left aside, what is dragged to the shore, as a simple example that transforming something means touching it very gently.

Santiago Villanueva

Curator, Public Programs and Education at MALBA

Santiago Villanueva (Azul-Argentina, 1990) is an artist and curator, living in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

He is a curator for Public Programs and Education at Malba [Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires]. He was in charge of the expanded area of influence at La Ene, Nuevo Museo Energía de Arte Contemporáneo [New Energy Museum of Contemporary Art (2011-2018) and curated the Bellos Jueves series at Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires (2014-2015). Between 2016 and 2017 he was appointed as educational curator at Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires. He coordinated 2019 Spazio de arte with Fernanda Laguna and Rosario Zorraquín.

El surrealismo rosa de hoy [Pink Surrealism of Today] (Ivan Rosado), Las relaciones mentales. Eduardo Costa [Mental Relationships. Eduardo Costa] (Museo Tamayo), Pintura Montada Primicia. Juan Del Prete [Primicia Mounted Painting. Juan del Prete] (Roldan Moderno), Mariette Lydis (Ivan Rosado), are among some of his books. He co-curated the exhibition Traidores los días que huyeron [Traitors the Days They Fled], by the artist Roberto Jacoby, at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Rosario, Argentina.

He was a member of the editorial group for Mancilla [Blemish] magazine. He is currently editor for Segunda época [Second Stint] magazine. He is a professor of Curatorial Studies at Universidad Nacional de las Artes (Argentina).