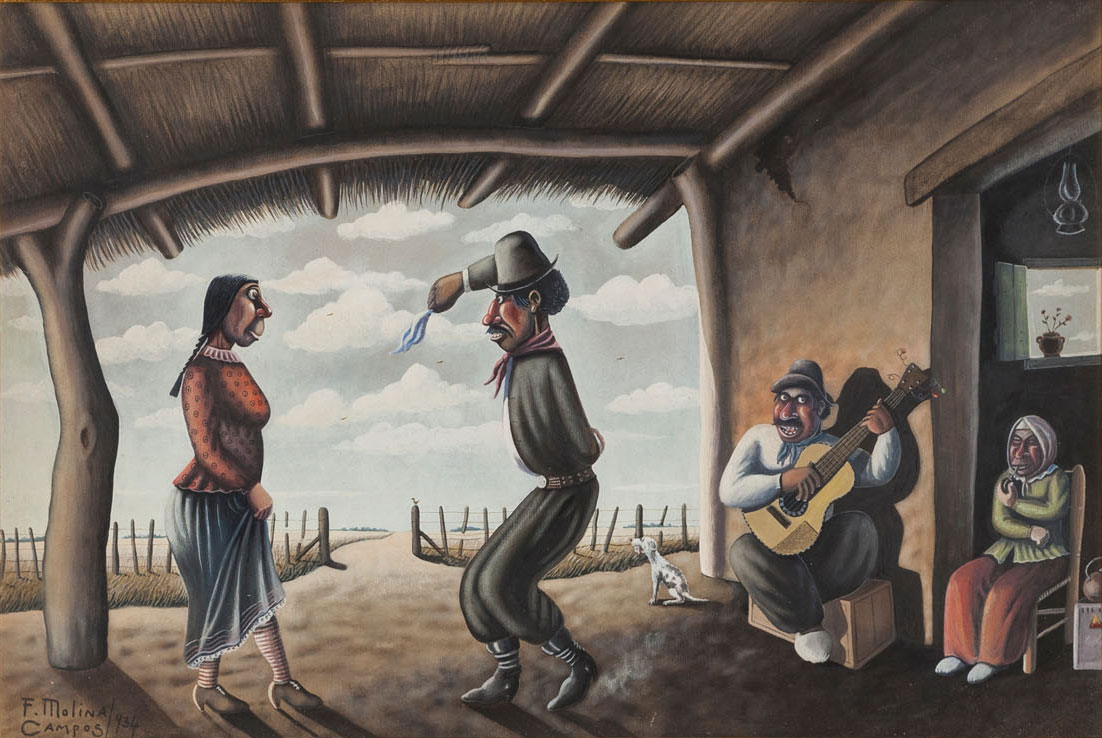

On Guitarreada (1926), by Florencio Molina Campos

Laura Isola

Ricardo Güiraldes published Don Segundo Sombra, the novel that attempted to renew nineteenth century gaucho literature in 1926, when the twentieth century had already begun with enough time to show other features of Buenos Aires´ modernization: not only the city, but also the countryside. It will be the text that tells in first-person the story of Fabio Cáceres' apprenticeship: from the age of fourteen and his memories as an orphan, to the conclusion and definitive separation from the gaucho Don Segundo, his guide in dressage and herding tasks in country life. Fabio's orphanhood is compensated by this idealized gaucho, his beloved stepfather, who bears all the country man´s virtues:

His chest was vast, his joints, bony and colt-like; his feet, short with a biscuit-like instep; his hands, thick and leathery like a hairy shell. His complexion, like a native; his eyes were slightly raised towards the temples and small. He pushed back his scanty-brimmed chambergo hat in order to talk more comfortably, revealing a fringe at eyebrow level cut like horsehair.

Don Segundo is surnamed Sombra [Shadow] and while representing that essential country man model, the word shadow bids some distancing. It is the ghost from that idyllic past that no longer exists: it is, little by little, the erasure of that figure to such an extent that part of literary criticism understood it as “the oligarchic landowners´ nostalgic and elegiac vision.” The end of the century aristocracy, with a modernizing project underway, the triumphant progress and the immigration course in accelerated growth, faced with the reality of an alien and unlivable city, look at the countryside with infatuation for that uncontaminated space, safe from the social changes that shake the cities. It is a new Arcadia without conflicts, some kind of uchronia both in images and in thought.

Florencio Molina Campos (1891-1959), like Güiraldes, paints a countryside that, in the last century´s twenties had ceased to exist. The modernization process had transformed those vast expanses of low and immense horizon into farms, economic units, power lines had crossed them, and trains were replacing wagons. He paints by heart something he cannot see. A happy world, without conflicts. Without malones [Indian raids] or armies. Without fires or persecutions: “I paint the gaucho, the one I have seen in bygone years, when real gauchos were still there, because I know and understand them. Soon, driven by progress and cosmopolitanism, it will be too late to copy them as they were.” He recommended, in turn: “I would say to writers, musicians, painters: go to the pampas, to the mountains, to the sierras and collect our immense dispersed flow, still in time to save our native folklore. It will be sad if future generations ask us to answer for it! It will be sad if we are not able to tell them what happened to the gaucho and what we have done to maintain our National Tradition!”

It is not either the nod of the writers who “went to the estancia” when life in the city became impossible, like a Babel in the Southern Hemisphere. Molina Campos does not take refuge in the countryside: he invents it once again. According to Luis F. Benedit (a painter and also a great specialist of his work), Molina Campos answers the great permanent question: what would have happened if the arriving immigration had not ensued, and everything remained like before. A world before immigration, with its ethics, its epics, is erased with the European country plan: “In Molina Campos there is a conception in this sense, although it is not xenophobic. The difference with Martín Fierro is that this text is contemptuous of immigrants. In Molina you are not going to see any immigrant doing a “noble” task, such as shackling, herding or branding cattle. Those depicted in his plates are natural countryside residents: the trinket seller, the pulpero [saloon manager], or the photographer, as in ¡Mirá lo pacarito, nena! [Look at the bird, baby!] And just as they are, they enter his happy world.”

Guitarreada [Guitar playing] combines several of these motifs. On the one hand, it confirms that happy world in the gaucho and his china [gaucho woman] dancing. In the style of painters Juan León Pallière and Prilidiano Pueyrredón, who produced their most important works after Rosas´ fall, the gaucho, identified with Rosas, ceased to be a threat after the leader´s downfall. Their labor force and their military service in the line of forts and the campaigns against the Indians became indispensable. The figures and situations are idealized. Pallière´s everyday scenes highlight the austere and peaceful atmosphere of life in the countryside that also boast a moral sense. In Idilio Criollo (1861) [Criollo Idyll], for example, the straw hut is in the foreground, the figures´ posture reflects the lovers´ modesty and good manners and the lady´s parents in semi-darkness reinforce the relationship´s public and crystalline character.

On the other, Molina Campos resumes the geography that recalls the old matrix inspired by traveling painters´ landscapes, that partition of space: three-quarters for the sky and the prairie´s low horizon, a peaceful and clean sky, a scene that proves the (imagined) countryside can still be painted.