On El incendio y las vísperas II, Beatriz Guido (1974), by Horacio Zabala

Gonzalo Aguilar

It happened in September 1972 in the city of Buenos Aires. A police patrol broke into Roberto Arlt square, located on Piedras and Rivadavia, and destroyed the works of art in the exhibition Arte e ideología, CAYC al aire libre [Art and Ideology, open air CAYC], which had opened the day before. Among the destroyed works was 300 metros de cinta negra para enlutar una plaza pública [300 meters of black tape to make a public square a place of mourning] by Horacio Zabala, a memorial for the people shot in the Trelew massacre. We do not know if the police officers were aware of what they were doing, or if they had any – even the slightest – idea of art. I imagine they were just following orders. Paradoxically, the work found one of its possible destinies in its destruction: to challenge power to the point of becoming intolerable and to exhibit with its presence/absence the closure of public space (and the need for actions to reopen or refound it). Acts of political violence had been ensuing at a vertiginous pace in the continent (death of Che Guevara, repression at Cordobazo, Aramburu´s kidnapping and murder), and art could decide to remain indifferent with its languages, finding refuge in its autonomy, or to subordinate itself to politics and its slogans. Horacio Zabala opted for another way out: a third, perhaps more arduous path, which was not comfortably established in the autonomy of art, nor in the univocal slogans of politics. The path was as follows: an undertaking that would be fed on conceptualism and constructivism, which would deploy his knowledge as an architect and that would make it drift towards irony – a bit Duchampian, true – but above all, very Zabalian. In other words: what happens when longstanding historical and pedagogical objects-concepts (the prison, the map, the newspaper) are placed under the action and under the artistic sensory viewpoint. “Art,” Zabala wrote in the early seventies, “depends on what is not art.”

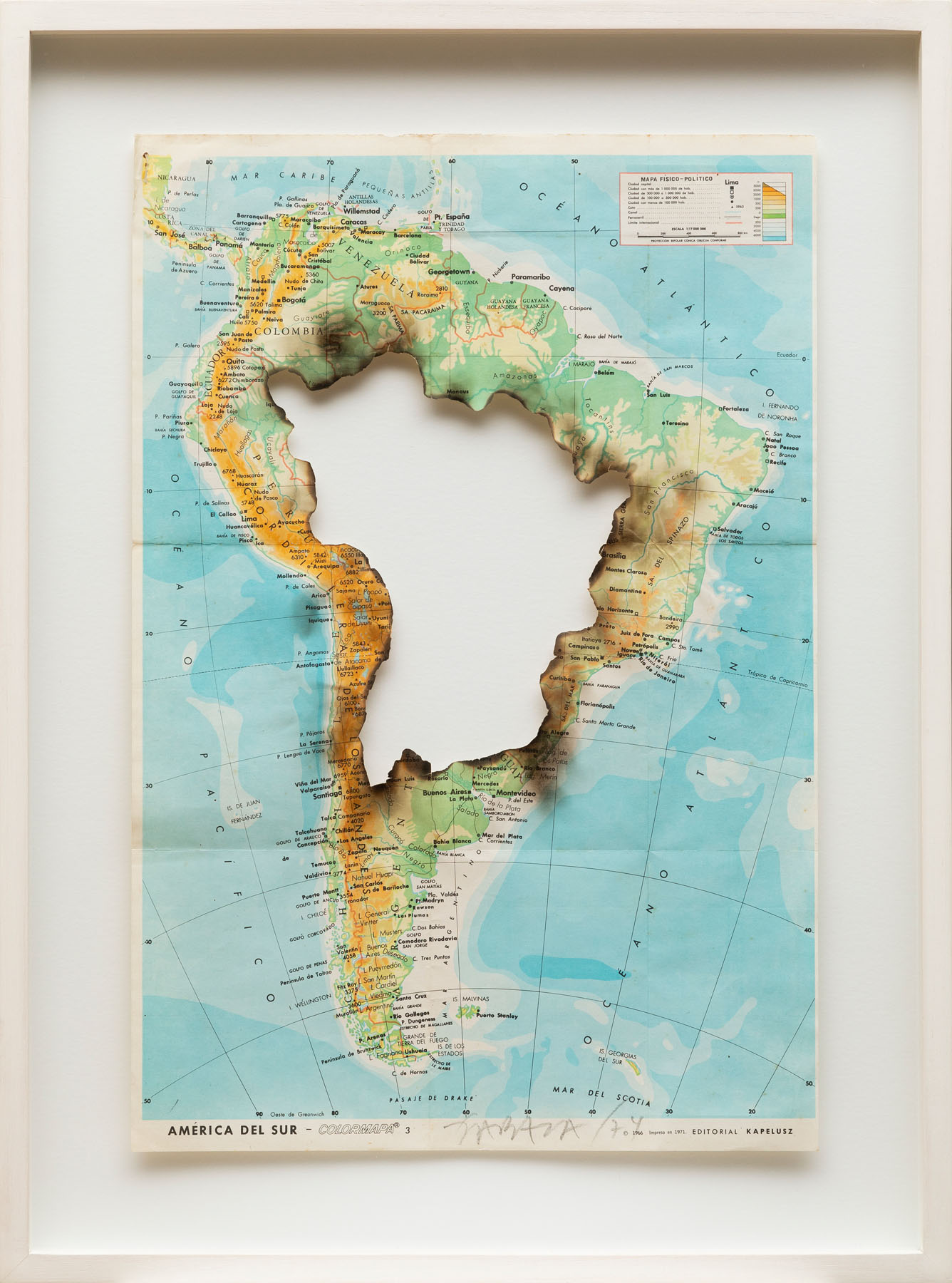

El incendio y las vísperas II, Beatriz Guido (1974) [Fire and Vespers II, Beatriz Guido] belongs to that experimental series blending conceptual and visual qualities. Zabala resorts to one of the school requests that have been very frequent in the past: “Tomorrow you must bring a map of South America, size 3, Kapelusz brand.” Then, the most diligent student asked: “Physical or political map?” “Physical-political,” was the answer. That is the one Zabala used in his work. It is an objective measurement image, to scale, a result of scientific knowledge, but it also allows poetic licenses such as the use of various black dots to indicate the amount of population in urban centers or colors for geographical features and borders. The raised zones are green for the areas at sea level (painted in light blue) and brown is used for the mountains. It is a convention inspired by the colors of nature, although partially false, since there are green mountains and brown plains, but our eyes got used to it. Zabala then takes this daily, educational, trivial, unexpectedly beautiful (I think so now) object and redeploys it from the Geography or Civic Instruction class to Practical Activities (that´s how they called the art teaching class). Then he forces three actions down to it: he gives it a title, redirects its pedagogy and hands it over to partial destruction and catastrophe.

Read from Marcel Duchamp´s strategies, a fundamental source for this Argentine artist born in 1943, the title resignifies the work and produces some noise or friction between the thing and the word. Zabala resorts here, as in other works, to literary texts. El incendio y las vísperas [Fire and Vespers] is a novel by Beatriz Guido published in 1964 about the fire at Jockey Club in 1953. It is critical of both Peronism and the Buenos Aires elite. The artist makes the fire real and yet dramatically symbolic. By detaching the term “vespers” from the narrative sequence, he fills it with omens: it is no longer the days before the fire (as in Guido's novel), but a specific event that, if you place yourself in the works´ composition date, could not be other than the Revolution that took place in Cuba and seemed to spread throughout the continent.

I do not think the map required in school was meant to show us the events that loomed in the continent. Zabala's work pierces the map with fire and on the silhouette´s edges the darkness of its passage remains. The act and the choice of the arising flare allow a political reading: the outline it leaves is formless, but it is centered on Bolivia. The “focus theory” that Che Guevara and Régis Debray held from Cuba, the idea that an insurrection would have a compelling effect, and it was necessary to “create one, two, three... many Vietnams,” impels the artist's gesture. Beyond the fact that the focus theory turned out to be false and even pernicious, El incendio y las vísperas II, Beatriz Guido has the virtue of igniting in the viewer a desire for rebellion, knowledge, and empathy.

How can we think about the catastrophe our daily condition resembles? One answer Zabala provides is to map it. Cartography and catastrophe: giving it a visual and conceptual, physical and political, sensory and sensitive dimension, but also open to meanings, because “art depends on what is not art” and, above all, on the passage of time. For this reason, we must not subordinate art to current politics, but rather open the power of the political that exists in art so that the viewer's gaze can perform its task.

Many years later, in Una serenidad crispada [A Strained Serenity], a show held at the MCMC gallery (Buenos Aires, 2022), the work was contemplated considering the rainforest fires in the Amazon and other places in Latin America as a result of agribusiness and climate change. A cultural supplement critic went as far as to call Zabala “an environmental catastrophe visionary.” The description is absolutely true, but only if we understand by “environmental” not only nature, but also art, politics, and the times we live in. Precisely, El incendio y las vísperas II, due to its openness of meaning and the way it transforms objects, is straddled in time, and admits, even encourages, new interpretations.