The common place

by Nancy Rojas

Curator, teacher, and essayist

Around 1926, in a letter addressed to Luis Ouvrard, Antonio Berni articulated his view about one of the central images in the Argentinian landscape: the pampa. He precisely told him: “...those pampas are anesthetic drugs for the spirit, instead, they are the place for technical advance...”1

In the light of this paradoxical vision of the Argentine plains that foresaw the necessary seed for progress in the flat surface, it is possible to ratify the way public figures in the city and the countryside were forging many complex deployments related to building a nationalist imaginary during the twentieth century. Many historiographical approaches to aesthetic modernism led to systematizing the polarity city-country, based on a logic that linked the image of the city with the idea of development, and that of the countryside with barbarism. This last connotation mutated later, when the countryside was subjected to a bucolic attribute, adept at capturing local traditions.

Sonia Berjman states that these interpretations lead to a “conceptual opposition,” implying that “the city is characterized by fullness, culture, progress, closure, movement, noise, change, stress, war...” and “the country is qualified as emptiness, nature, stagnation, openness, stillness, silence, permanence, relaxation, peace...”.2 This trend obstructed the possibility of thinking about the anchors, the socio-economic resonances and the exchanges between both elements very often. Considering that during the nineteenth century the pampas constituted a territory inherent to the fatality of the conquest, the countryside and the city could be read from the processes that were part of the same transcendental and heterogeneous phenomenon of modernization, with its proximities and distances, rather than as two completely antagonistic universes. In this sense, thinking from the Santa Fe province context, Adriana Armando points out that the “constant growth of the city widened the suburbs, created increasingly impoverished margins and distanced from the planes of ploughed land.”3 This situation, rather than implying a polarization of these public figures in a modernity-tradition debate, led to channeling certain artistic productions towards other panoramic frequencies, diversifying and complicating the notion of “plain” in the artworks.

On the other hand, the countryside and the city are symbols of a productivity system that early on foretold the destiny of the current capitalist gaze. And this is a factor that also implied and should continue to imply a critical look at the way in which the Argentine landscape is ideologically thought and formed.

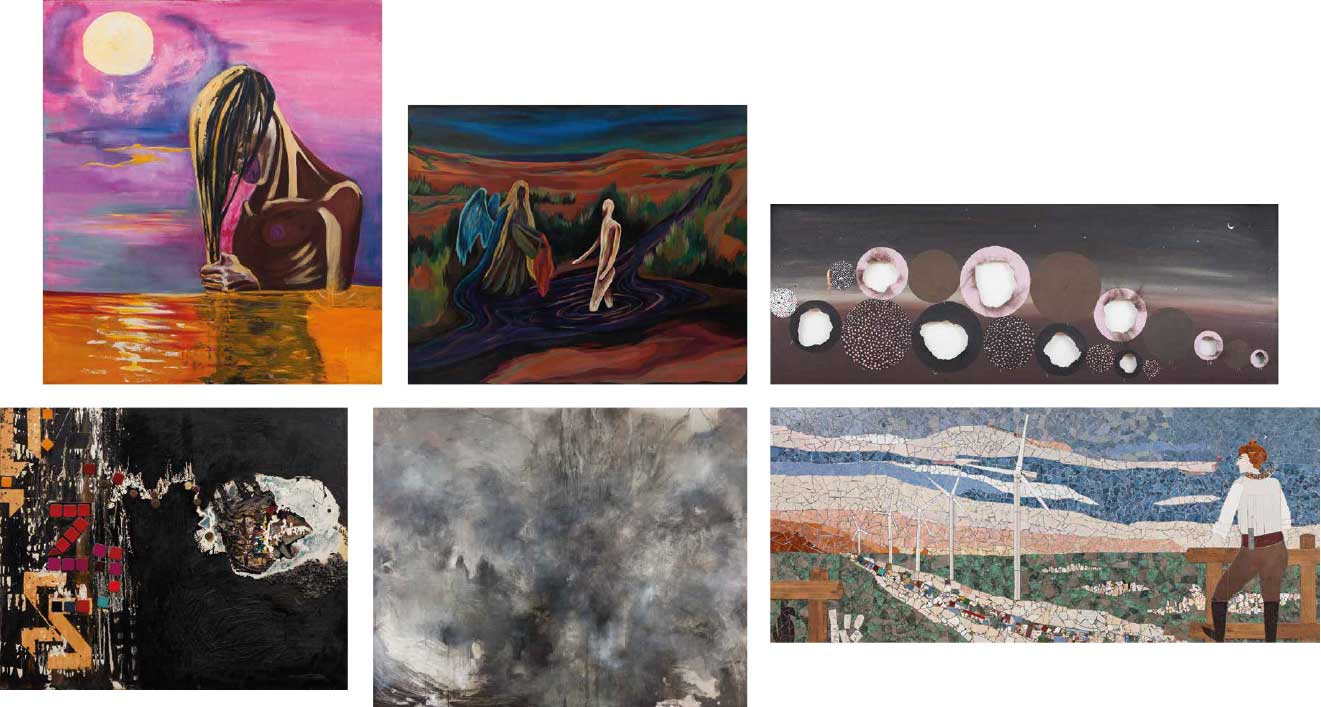

For the artists, this genre meant a space of imagination and the proliferation of an avant-garde perspective, where not only visual but also philosophical and political ruptures were forged. Towards the middle of the twentieth century the landscape enabled a total experimentalism that portrayed some kind of disturbed geography, to show that the landscape was going to keep being one of the aesthetic keys to investigate both lack and excess, in the estranged, utopian, completely fictionalized reality, in stillness and also in mutation. We can then talk about the existence of another sphere of production within this genre, destined to obstruct the idyllic notion of landscape while also collaborating with the challenging task of assuming a detour in the conception of nature. Within Colección Pampa, Marcia Schvartz’s production can be read in these terms. Her Nocturno [Nocturne], from 1994, brings back the image of water in the landscape. In it, solitude insists on the sordidness of a rebellious and lunatic immensity, where a female character fills this Fauvist-attributed representation with eroticism. Schvartz's work eradicates any kind of idyllicization by situating itself in a matter-evoked frenzy through chromatic intensity, appealing to a corporeality that copulates with the earth insisting on the poetic and political power of brown.

Schvartz, Marcia Nocturno 1994 Óleo Sobre Tela 140 x 160 cm

Ana Clara Soler also works with this color pattern in a series of paintings she made in 2008, but the method is different, because in this case the starting point is the semi-darkness, absolute black. In this series, the artist paints her canvases in black to emerge from the shadow into the light through color. But in Sin título [Untitled] there is also another peculiarity: religious iconography. A narrative germ leads us to the obvious links in the new realism images revealed by historian Guillermo Fantoni, where artists such as Antonio Berni elaborate their stories based on scenes from Western art history, focused on Christian references.4 In this case, Ana Clara Soler first painted a watercolor where she captured the story and then carried out the painting. A version of the Annunciation where a character comes out from the center of a lagoon to meet the figure of an angel. Her statement is based on the analogies rooted in the existing connotations of “coming out of the water” through a tactic to flow out from black to luminescence, to color.

Soler, Ana Clara Bienvenida 2008 Oleo Sobre Tela 105 X 130 cm

Both in Marcia Schvartz's and Ana Clara Soler's pieces, the standard notion of landscape explodes in an ominous and gloomy nocturnality, and it does so by configuring a pictorial state close to fluorescence.

With a more abstract key, we can place our gaze on another nocturne of Colección Pampa: La noche [The night], 1963, by Jorge de la Vega. An Informalist painting from his Bestiario [Bestiary] series, where gloom is present not only through the use of black and gestures, but also in the presence of a monster floating on the surface. This monster, as in the case of the characters in Ana Clara Soler’s painting, also emerges from darkness.

De la Vega, Jorge La Noche 1963 Óleo Sobre Tela 81 X 100 cm

But nocturne as an aesthetic genre approached from an earthly point of view is not the only space to pose a more reserved vision of the landscape. The works that refer to clouds, to supraterrestriality, are also part of what Victoria Cirlot identifies as the “negative imaginary of nocturnality,”5 where the immeasurable is historically associated with the unknown, something that cannot be reached in a visible way.

Rosario Zorraquín is based on the cloud form, a pattern that for Cirlot precisely forms one of the elementary bases to activate imagination. Based on a study of clouds developed by artist Johann Georg von Dillis between 1800 and 1820, this theorist warns that clouds make you learn about “dissolution of forms […] how the forms of the formless are generated and how forms are dissolved and, with forms, how identities are dissolved”.6 Las nubes [The Clouds], painted by Zorraquín in 2010, condense degrees of possibility and pictorial mutation insofar as they are subject to compression and explosion at the same time. And from this material imprint they assume a surreal force as a condition of their subliminal temperament. We can underpin that the performative factor of this work brings into focus a specific tradition of painting, the one that seeks transcendence, believing in the anarchy of glaze and predicting moments of dissipation, dripping and permanent staining.

Zorraquin, Rosario Nubes 2010 Acrilico sobre tela_Alta

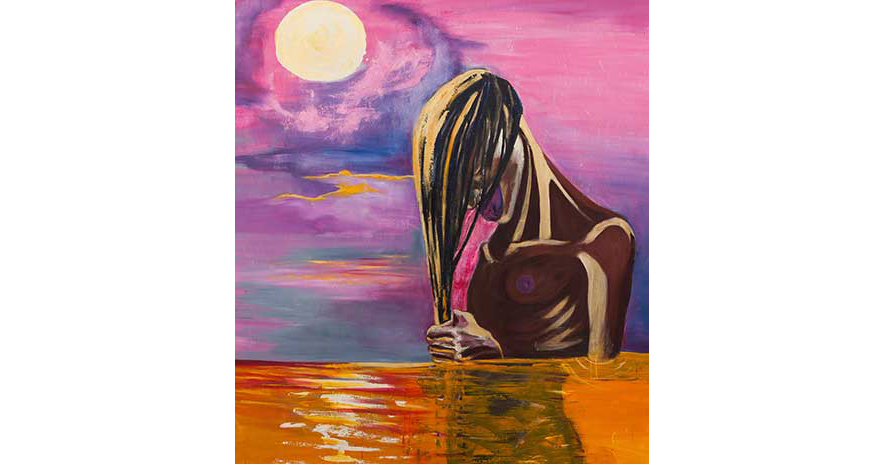

Another projection of this same perspective leads us to Fernanda Laguna's Cosmos, part of a series of artworks started in 2008. It also integrates this nocturnal imaginary, but there is a different quality here. The base for the image is perforated and this breakage gives an extension of vacuum back to this piece. The use of a brown palette foreshadows cosmos, not necessarily affirmed in the celestial, but rather in an earthy dimension, which paradoxically unites it with the center of the earth.

Laguna, Fernanda Cosmos 2008 Técnica mixta sobre tela 65 X 140 cm

It could be then an earthly cosmos, which suggests commonplace, non-grandiloquence, irregularity, and eccentric poetry within the framework of Laguna's characteristic trash aesthetics.

Therefore, in the developments of contemporary art, landscape as a construction has numerous drifts nowadays. For some artists, there is no room for a sedate and bucolic vision, but a dark and chimerical approach where order is not subject to vastness but nocturnality, to the other, to the eroticism of color and dissolved form, to the fusion between human and non-human corporality and sometimes between the earth and the supra-earthly whole. From this plane we can affirm that these artworks do not seek a representation of nature, but a pictorial experience of it. A few years ago Donna Haraway pointed out:

Nature is not a physical place to which one can go, nor a treasure to fence in or bank, nor as essence to be saved or violated. Nature is not hidden and so does not need to be unveiled […] It is not the ‘other’ who offers origin, replenishment, and service. Neither mother, nurse, nor slave, nature is not matrix, resource, or tool for the reproduction of man.7

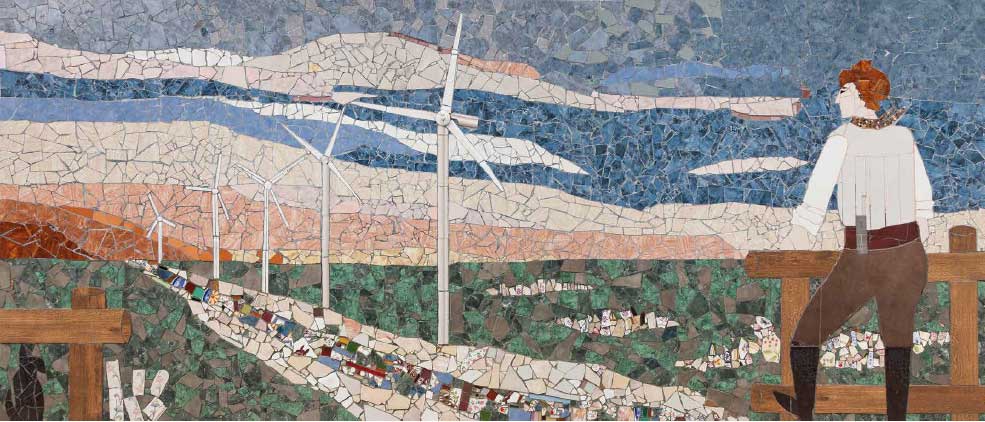

The author intends to consider nature as ‘commonplace,’ “effected in the interactions among material-semiotic actors, human or not.” 8 This network of pieces can be considered, from this point of view, as a possible gaze to exert an escape from any notion that implies a purified representation. Precisely in order to appeal to a distinctive look at nature that can even lead to an exercise in landscape de-romanticization, capable of reviving the validity of a more queer, more diverse nature, of fusions and not of separations. Inadmissible similarities and abject spaces, unfinished warps and wefts, dull and dismembered lands, pictorial and sign performativity can be found in this detour, but also pause and otherness, as happens in the site-specific El descanso [The Break], 2015, by Nushi Muntaabski.

Muntaabski, Nushi El Descanso 2015 Cerámica sobre pared superficie 12 m2.

1 Antonio Berni, letter to Luis Ouvrard dated Segovia, June 2, 1926, unpublished manuscript, Ouvrard Archive. Cited in: Ouvrard: pinturas y dibujos 1916-1986, Rosario, Editorial Municipal de Rosario, Iván Rosado, 2016, p. 21.

2 Sonia Berjman, “Buenos Aires: el campo y la ciudad”, Ciudad/Campo en las Artes en Argentina y Latinoamérica, III Jornadas de Teoría e Historia de las Artes, Buenos Aires, CAIA, 1991, p. 21.

3 Adriana Armando, “Silenciosos mares de tierra arada”, Studi Latinoamericani # 3, Udine, CIASLA/FORUM, 2007, p. 373.

4 Guillermo Fantoni, Berni entre el surrealismo y Siqueiros. Figuras, itinerarios y experiencias de un artista entre dos décadas, Rosario, Beatriz Viterbo, 2014.

5 Victoria Cirlot, Imágenes negativas. Las nubes en la tradición mística y la modernidad, Viña del Mar, Mundana Ediciones, 2017.

6 Victoria Cirlot, La visión y la creación artística: de Hildegard von Bingen a Max Ernst, lecture given at V Encuentro Arte Pensamiento, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Fundación Cristino de Vera, Espacio Cultural Caja Canarias, November 27, 2014

7 Haraway, Donna. “The Promises of Monsters: A Regenerative Politics for Inappropriate/d Others,” Cybersexualities: A Reader in Feminist Theory, Cyborgs and Cyberspace, 2019, pp. 315–316.

8 Haraway, Donna. “The Promises of Monsters: A Regenerative Politics for Inappropriate/D Others,” Cybersexualities: A Reader in Feminist Theory, Cyborgs and Cyberspace, 2019, p. 318.

Nancy Rojas (Rosario, 1978) is a curator, teacher, and essayist. She has conducted several research, performative and curatorial projects, and co-founded spaces such as Roberto Vanguardia (2004-2005) and Studio Brócoli (2006-2014). She was appointed curator of institutional exhibition programs such as Salón Nacional de Artes Visuales at Casa Nacional del Bicentenario (2019), Quincena del Arte de Rosario (2019) and Isla de Ediciones space at arteBA (2018), and as general curator at Castagnino+macro museum (2012-2013), where she was also in charge of the Acquisitions Program that furthered the Colección de Arte Argentino Contemporáneo (2004-2011). As a curator, she also had exhibitions in galleries and museums, with essays about current symptomatic crossings between queer culture, its micropolitical drifts and contemporary images. She is the author of Mugre severa [Severe Filth], published by Caracol (Buenos Aires, 2021), essays and research for graphic media, catalogs, and books by Argentinean publishing houses. She won the José León Pagano Prize in 2007 for a group exhibition by local artists at Asociación Argentina de Críticos de Arte, a space she is currently a member of.