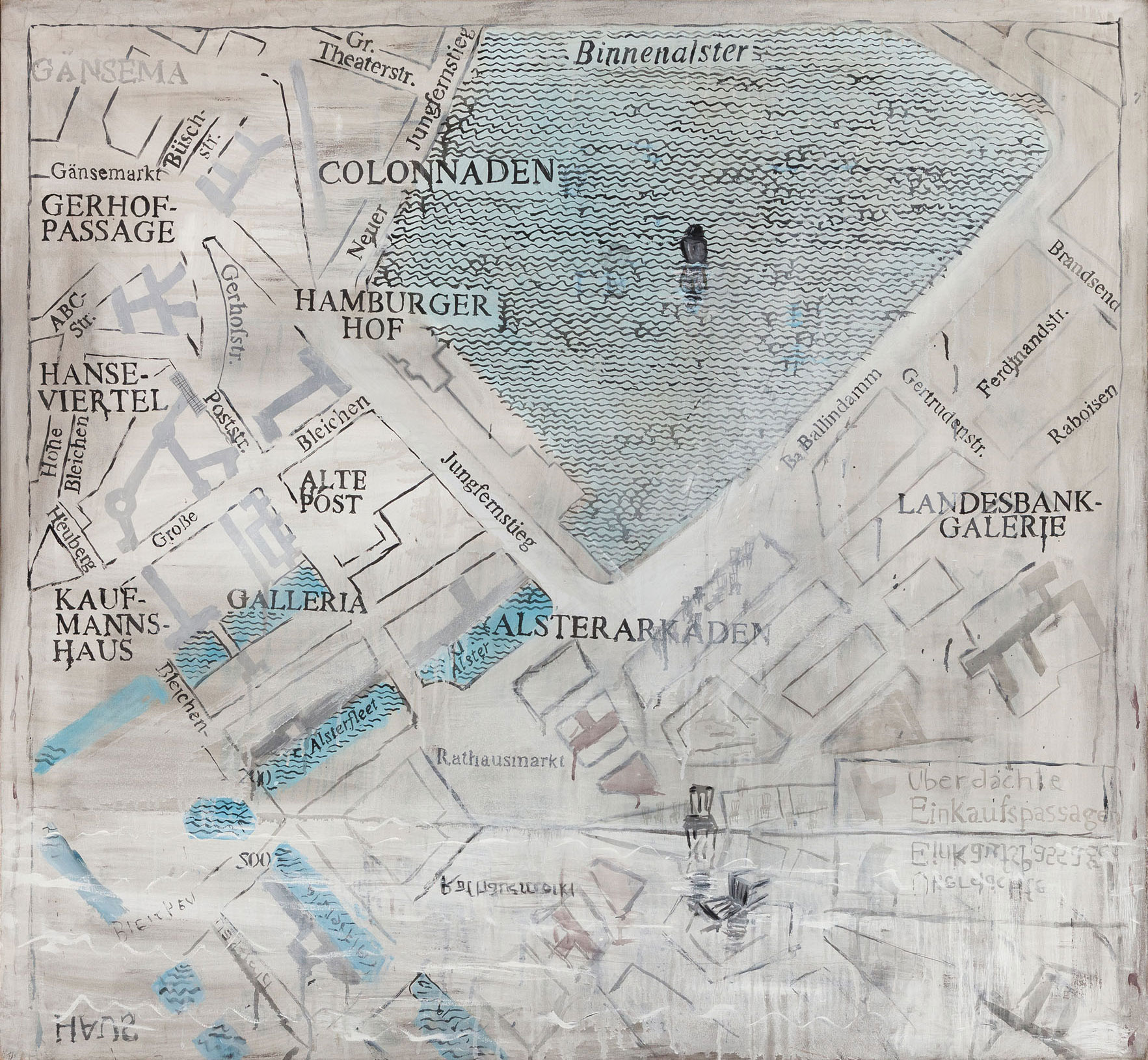

On Hamburg (1987), by Guillermo Kuitca

Graciela Speranza

The city of Hamburg has no shortage of attributes to stand out in the great planisphere of the world. It is one of the most populous cities in Germany and the second most important port in Europe. In the heart of the city, two artificial lakes dam the Alster River waters, and nearly 2,300 bridges cross over its canals, more than those of Venice and Amsterdam combined. Devastated during the Second World War, it stubbornly rose again, and continues to vibrate today under the Nordic fog, with the sirens of ships and the squawking of seagulls you can imagine just by looking at the plan.

But it is likely none of these things were relevant when choosing Hamburg in Hamburg (1987), among the plentiful series of city plans and road maps that Guillermo Kuitca painted since the late 80s. Certainly, the young Kuitca traveled to Germany for the first time at the beginning of that decade, following the Pina Bausch company that dazzled him in Buenos Aires and would leave a clear footprint on his work. He then imagined that, like the dancers who renounced classical ballet to join Bausch´s particularly personal dance, he could also renounce painting as he had cultivated since childhood; perhaps even “dancing the painting,” as Isadora Duncan wanted to “dance an armchair.” He arrived just in time to attend Pina Bausch´s Bandoneon last performance in Wuppertal. And although it is also true that a few years later he visited Hamburg, the choices that guide his personal cartography are almost never dependent on biographical traces, nor on historical or political echoes.

The first map was Prague in 1987, and ever since he painted maps of cities far and wide, urban plans with blocks delineated by bones, thorns, needles, cutlery or swords; road maps of Italy, Afghanistan or China, and even star maps, in a protean and proliferating atlas composed at random, by the sound of the city names, colors, shapes, or simply the interlacing lines, signs, and words´ visual texture. After his early 80s first series – Nadie olvida nada [Nobody Forgets Anything] with their beds and back-turned women, the theatres in El mar dulce [The Sweet Sea] and Siete últimas canciones [Seven Last Songs] – the map revealed itself as an infinitely appropriable paradoxical image, the most accurate representation of the world and all at once the most abstract. A fountain of unspoken metaphors. Enraptured in front of the map on the canvas as if no one ever painted it before, Kuitca added it to his discreet vocabulary and subtracted the human presence. And even though maps seemed to have disappeared from his works in the early nineties, they returned again and again as an inexhaustible material, as the streets and routes crossing the world, or the turmoil and blasts shaking it.

But for some reason (echoes of the legendary birth of The Beatles at San Pauli, this same city´s rogue neighborhood?), Hamburg reappeared in many works like a ritornello, slipped into other series, stood out in the spider´s web center the routes weave on the map, doubled vanishing in a gold and silver diptych, merged with his classic apartment floor plan, and it was even chosen in his Coming (1989), where he composed the progressive estrangement of his painting from the intimacy of beds, apartments and theaters, to the abstract figuration of city plans and road maps.

Hamburg (1987) is an eloquent work in this journey, as it witnesses the painter going from one series to another, refining his repertoire, reinventing himself with each advance and nevertheless forgetting nothing. The copy of the city plan is true, with a cut-out surely encouraged by the old downtown streets´ broken geometry, and also by the blue planes of the canals and the lake, which interrupt the gray and dense urban grid texture with the bodies of water´s suggested waves. But if you look closely, there are two presences breaking it up from its conventional representation and transforming it. Kuitca makes it unmistakably his own with a wash at the bottom that mirrors it and gives three dimensions to the whole, as if it were a stage where two chairs snatched from his theaters happen to populate the city in a dramatic scene. But there is another, almost surreal, even more curious presence. A tiny back-turned woman, as those who crowded Nadie olvida nada [Nobody forgets anything] suspended in the air, appears submerged in the lake here. Kuitca only leaves the scene prepared with a duplicated plan, leaves the woman half submerged in the water, leaves a chair standing and another chair fallen, and says nothing. In those slight realignments that make a map remain a map and yet it is transfigured, the persistent mystery of Kuitca´s painting is nested, which can make a scene take shape, the beginning or the end of a story to be barely hinted at, the canvas become a map, a theater and an elusive narration, without leaving the pure resistant plane of the painting.

Prodigies of art. A few years later, in Naked Tango (After Warhol) (1994), Kuitca was even able to dance the painting.